Discovery and demise of a new species of Magnolia from northern Peru, South America

Panoramic view of Alta Mayo valley in Peru.

Michael O. Dillon, Curator Emeritus, Botany Department, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL Note: This article originally appeared in Magnolia, the Journal of the Magnolia Society International, Volume 47, Issue No. 91 (Spring/Summer 2012). Become a member of the Society today to receive the Magnolia journal.

The eastern side of the Peruvian Andes is home to some of the highest biological diversity on Earth. As one travels east across the mountains and crosses the continental divide, the montane forests and the ceja de la montaña (the eyebrow of the forest) give way to the lowland rain forests of the Amazon basin. These forests are termed Selva Alta and range roughly between 500-1500 m (150-450 ft). One area in particular, the Alto Mayo river basin in the northern San Martín, is distinctive for having high bird diversity and highly endemic, threatened primate species, such as the yellow-tailed woolly monkey (Oreonax flavicauda) and Rio Mayo titi monkey (Callicebus oenanthe). It has also been long known that this region is home to considerable flowering plant diversity. It was not until the area was opened up by passable roads into the interior in the 1970s that the extensive forests of the basin became easily available to modern botanists.

In the mid-1500s, the forests were continuous from northern Bolivia to southern Ecuador. The city of Moyobamba, just south of Rioja was founded by the Spanish in 1540 on the borders of the Río Mayo. From that time forward, disturbance has eroded the integrity of the forests. The same roads that made the forests accessible to botanists also made the area popular for immigration from other regions of Peru, especially from the Sierra to the west. Over the last 50 years, the population of northeastern Peru has grown rapidly and this growth has resulted in the further exploitation of unprotected forests. In 1986, amid fears that continued logging would directly threaten their watersheds or “micro-cuencas," local leaders in Rioja requested that the forests in the headwaters of the Río Alto Mayo and its tributaries be protected. In that year, the Peruvian government set aside a large portion of these forests under the protected status of Bosque de Protección Alto Mayo; it amounts to an area about half the size of Rhode Island (~700 mi2), covering the watershed of the Río Alto Mayo. However, while the forests are protected under law, there is no enforcement mechanism for keeping settlers out and preventing illegal lumber extraction.

In 1994, against the backdrop of continuing destruction of the forests within the protected area, The Field Museum initiated a collecting program largely within the boundaries of the park. My Peruvian colleague, Dr. Isidoro Sánchez-Vega, Director of the herbarium at the Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, and I actively explored and collected over the next seven years (Dillon & Sánchez, 2001; Sánchez et al., 2002). Field studies were challenging, with difficult terrain cut by a few narrow trails, most no more than two feet wide, and depending upon the season, extremely slippery and filled with muddy, knee-deep holes that literally suck your rubber boots off. On these trails with their steep switchbacks, the locals and their pack animals traverse the hills a few hundred feet high.

In 1994, against the backdrop of continuing destruction of the forests within the protected area, The Field Museum initiated a collecting program largely within the boundaries of the park. My Peruvian colleague, Dr. Isidoro Sánchez-Vega, Director of the herbarium at the Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, and I actively explored and collected over the next seven years (Dillon & Sánchez, 2001; Sánchez et al., 2002). Field studies were challenging, with difficult terrain cut by a few narrow trails, most no more than two feet wide, and depending upon the season, extremely slippery and filled with muddy, knee-deep holes that literally suck your rubber boots off. On these trails with their steep switchbacks, the locals and their pack animals traverse the hills a few hundred feet high.

We conducted forays on foot for 1- to 2-week periods throughout the park. Food and shelter had to be carried on one’s back unless mules could be secured. And alcohol had to be carried, but mostly not for drinking. Rather, since conditions did not permit the initial drying of plants, they were pressed into newspaper, bundled into heavy plastic bags, and saturated with alcohol, often strong, local “whitelightning” cane liquor. When we returned to our base of operations in Rioja, we dried the plants in presses with aluminum corrugates and electrical heaters.

While lower level vegetation is easy to sample, trees present special problems and challenges. With the aid of clipper poles that extend to 36 feet, and some younger locals willing to climb trees, we were able to sample trees whose first branches were more than 20 feet above the base. Flowers and fruits are mostly hidden in the canopy, well over 50 feet from the forest floor. Trekking through the forests, one quickly learns to look down first, encountering flower parts or fruits on the forest floor, and then looking up, to try to associate which large tree was shedding its reproductive structures. Most trees seemed to have quite small flowers in relation to their size; i.e., the bigger the tree, the smaller the flowers! Most species, in fact, had remarkably non-showy flowers. There were plenty of orchids festooning off branches and trunks, but only a few showy flowers from trees. We did not expect to encounter any Magnoliaceae. The family was not treated by MacBride in the Flora of Peru series or by Brako & Zarucchi (1993). Species had been recorded for Peru; for example, Magnolia amazonica (Ducke) Govaerts and M. rimachii (Lozano) Govaerts from the lowlands or Selva Baja. However, the family was anything but common in the Peruvian Selva Alta.

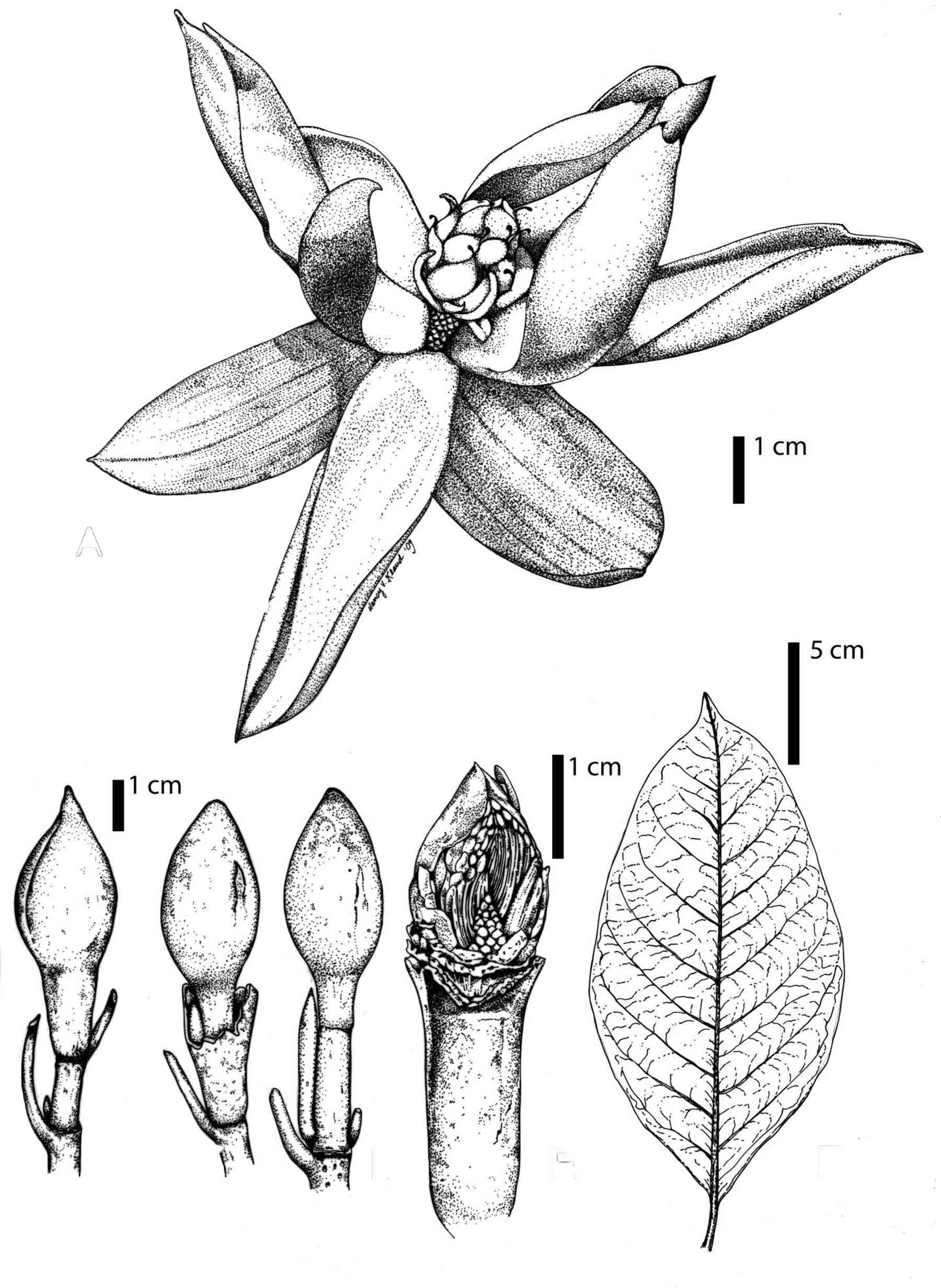

Imagine our surprise, on a June day in 1998, as we trudged up a slope covered by mixed evergreens above the Río Serranoyacu between the villages of Aguas Verdes and Paraiso, and spotted a small tree with shiny, dark green leaves and a single, large white flower with petals nearly 6 cm (+2 in) long. Despite concerted efforts to locate another individual or another bloom, none were found on that trip. At the time, we were quite excited about finding what we took to be a new species of the Magnolia segregate Talauma and discussed collecting what was obviously such a rare plant. Since there was only the one flower, we decided to collect a unicate and return another time to see if there were more blooms to be had. When we returned in less than six months time, that tree and most of the forest around it had been cut. The following year in July, we found another individual between Aguas Verdes and Perla del Mayo. We collected it, but it was sterile and we never encountered another plant during subsequent years of exploration. We put off the description of the new species, wanting to wait to find more flowering material before beginning a formal description. And when we wanted to explore its relationships, we discovered our material that had been treated with alcohol was not suitable for DNA extraction.

Imagine our surprise, on a June day in 1998, as we trudged up a slope covered by mixed evergreens above the Río Serranoyacu between the villages of Aguas Verdes and Paraiso, and spotted a small tree with shiny, dark green leaves and a single, large white flower with petals nearly 6 cm (+2 in) long. Despite concerted efforts to locate another individual or another bloom, none were found on that trip. At the time, we were quite excited about finding what we took to be a new species of the Magnolia segregate Talauma and discussed collecting what was obviously such a rare plant. Since there was only the one flower, we decided to collect a unicate and return another time to see if there were more blooms to be had. When we returned in less than six months time, that tree and most of the forest around it had been cut. The following year in July, we found another individual between Aguas Verdes and Perla del Mayo. We collected it, but it was sterile and we never encountered another plant during subsequent years of exploration. We put off the description of the new species, wanting to wait to find more flowering material before beginning a formal description. And when we wanted to explore its relationships, we discovered our material that had been treated with alcohol was not suitable for DNA extraction.

In June, 2008, we returned to the upper Río Alto Mayo valley specifically to attempt to relocate the Magnolia species in the forests near Aguas Verdes. The idea was to get some suitable material for DNA analysis. We were dismayed to find that the forests had been clear-cut and planted in coffee. We found the beginnings of a road being constructed within the park that will make extraction of resources easier. When we inquired about such trees, the ones with large white flowers, the locals were of no help in locating them, denying their existence. They take the view that such plants are actually “dangerous” to their livelihoods as madereros, or lumber extractors. Like the various rare and endangered birds and primates in the region, scientific study shines a glaring light on the locals’ most destructive practices. The Alto Mayo region is a protected area, but lacks any real protection from those who are responsible for providing it.

At that moment, we decided to go ahead with the description of a new species of Magnolia, given that Talauma had been found nested within Magnolia in the light of molecular investigations (J. Wen, pers. com.). We feared that it was extirpated in the type locality and waiting for further material might prove impossible. By describing the new species as beautiful and obviously threatened, we felt that it was emblematic of all organisms in this habitat, and might provide some small amount of publicity about the plight of the forests. This handsome new species is named in honor of Susan and James Bankard, longtime patrons of science at The Field Museum and supporters of our ongoing efforts to record and document Peru’s endangered plant life (Dillon & Sanchez, 2011).

Postscript

In November 2009, I was in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, monitoring El Niño influences when I received an email from Richard Figlar, inquiring about a potential new species of Magnolia from Peru! He had been contacted by Russian botanists, who, while traveling in the Alto Mayo region studying palms, had encountered a photograph of a Magnolia flower attributed to me and published in a 2009 calendar for the Universidad Privada Antenor Orrego (Trujillo). I was able to forward a proof copy of the new species publication and eventually hard copies of the journal, Arnaldoa, printed in Peru. We are hopeful that the species is not extinct, just hiding in the remaining forests and we will continue our search in the future.

Acknowledgements

Funding for fieldwork was provided, in part, by the National Geographic Society Grant 5791-96 and The Field Museum. I thank Isidoro Sánchez Vega, Mario Zapata, Ro- Mario Zapata, Roberto Diéguez, Segundo Leiva, Víctor Quipuscoa, Manuel Cabanillas, Julio Hidalgo, Hugo Vela, Arquilo Vargas, Emerson Vargas, and Lalo Martell. Nancy Klaud is acknowledged for her illustration. I also want to thank Richard Figlar, who originally contacted me about the image on the calendar and ultimately suggested that this short story of the discovery and plight of an endangered Magnolia might be of interest to the members of the Magnolia Society International.

Literature Cited

Brako, L. and J. L. Zarucchi. 1993. Catalogue of the Flowering Plants and Gymnosperms of Peru. Syst. Bot. Mongr. 45. Missouri Botanical Garden. 1286 pp.

Dillon, M.O. and I. Sánchez-V. 2001. Floristic Inventory of the Bosque de Protección del Río Alto Mayo (San Martín, Peru) URL: http://www.sacha.org/ envir/eastlow/intro.html.

Dillon, M.O. and I. Sánchez V. 2009. A new species of Magnolia (Magnoliaceae) from the Alto Mayo region, San Martin, Peru. Arnaldoa 16(1),7-12.

Sánchez-V., I., G. Iberico-V., M. Zapata-C., M. L. Kawasaki and M.O. Dillon. 2001. Nuevos registros para la flora de San Martín, Perú. Arnaldoa 8(2): 45- 52.

Magnolia Journal

To keep abreast of the latest developments in the world of magnolias, including articles like this one, join the Magnolia Society today and receive a subscription to Magnolia: The Journal of the Magnolia Society International.

About the Author

Michael Dillon Curator Emeritus, The Field Museum

Learn more about Michael Dillon's research at the Field Museum in Chicago, IL.